-

Choosing Study Books

-

Summer Schools

-

The "B" Word

-

Articulation

-

Food For Thought

<

>

I recently talked about study book repertoire in my Talking Flutes Podcast.

Here is my recommended list of Exercise, Workbooks and Study Books.

TONE DEVELOPMENT BOOKS

Moyse: De La Sonorite

Moyse: Tone Development Through Interpretation

Philippe Bernold: La Technique d’Embouchure (Published by La Stravaganza)

Peter Lucas-Graf: The Singing Flute

Clare Southworth: The Expression of Colour (Astute Music)

Robert Dick: Tone Development Through Extended Techniques

FINGER TECHNIQUE BOOKS

Moyse: Studies and Technical Exercises

Technique and Chromaticism

Scales and Arpeggios 480 Exercises

Daily Exercises

Geofrey Gilbert: Technical Flexibility

Moshe Epstein: Mind Your Fingers (Zimmermann)

ARTICULATION

Moyse: School of Articulation

50 Variations on the Allemande of Bach’s Aminor Solo Sonata

SEQUENCE BOOKS

Taffanel and Gaubert: Daily Exercises

Reichert: Daily Exercises

Andre Maquarre: Daily Exercises

Daniel S, Wood: Studies for Facilitating the Execution of the Upper Notes

Geoffrey Gilbert: Sequences

Boehm: 12 Studies

Southworth: Sequentials

GENERAL WORKBOOKS

Southworth: Flute Reboot

Flute Aerobics

Light Aerobics

Peter Lucas-Graf: Check-Up

Moyse: How I Stayed In Shape

GENERAL STUDY BOOKS

Moyse: 24and 25 Melodious Studies

Boehm: 24 Caprices

Sousseman: 24 Studies

Altes: 26 Studies

Anderson: Opus 15 and 63

Piazolla: Tango Etudes

Karg-Elert: 30 Caprices

Damase: 24 Studies

Lorenzo: Caprices

Paganini: 24 Caprices

Krystof Zgraja: 3 Virtuosic Flamenco Studies

Mike Mower: Finger Busters

Lorenzo: 9 Grosse Studies

Summer Schools and How to Choose

There are two main points to consider:

- Summer schools give the opportunity for students to learn from experts in their field of interest.

- These courses are in the holiday period and the people attending are on their holidays! Something that’s often forgotten.

They all offer something different.

First you have to decide what you want to get out of it and then do some research.

You may be an enthusiastic adult learner, or a school age student wanting to take flute further or already a college student, wanting to hone your skills.

Some thoughts to consider:

Who are the teachers?

What is on offer?

What are the costs? Tuition/accommodation/food.

Be wary of the costs being broken down – it adds up very quickly.

How many lessons and what sort of lessons: private/masterclasses/workshops.

What abilities are catered for?

What sort of environment? What else is offered?

Many students go for their holidays as well as a learning experience. Are there activities organised outside of the classes? What happens in the evenings? Are young players supervised?

There are students though that just want intensive tuition at the highest level.

Let’s look at serious courses.

These are good for judging how well you play in comparison to your peers. So if you are about to audition for music college, then this is a good time to see what some of the competition is doing.

It is also a good opportunity to play and learn from tutors at the music colleges, and get advice about auditions, practice, repertoire.

They help you to make informed choices.

On my course, I always had tutors from different colleges, Royal Northern, Guildhall, Trinity and the Academy.

If you are an enthusiastic amateur, make sure you search out the information that will help you choose. Ask questions about age range, ability range, what lessons are available and with whom you get lessons. Are there enough playing opportunities in choirs and chamber music.

Don’t assume that because you are attending a course with a top professional that you will get lessons from that person. Many courses have assistants.

I always prided myself on offering lessons for all ages and all abilities. No discrimination.

Summer schools can be quite intense, but often there is a close knit class of like-minded students and you learn more from listening than playing, because you are more relaxed when listening and able to absorb the information.

A musician’s every day life can be a lonely one, many hours practising on your own. Summer schools give the opportunity to meet other like-minded students, a chance to chat and discuss all flute related problems.

You can hear more information in a week than in a year of lessons. But, you need to act on that information after the course. So make loads of notes and use them during the year.

I started my own flute course in 1986 in the Lake District. I had so many ideas on how to run a successful course having had many years experience on the International Flute Summer School.

That was a very successful course in the late 70’s and early 80’s, but not for everyone. Emphasis was on the top players. It was a highly competitive course, where every student had to audition when they arrived and then they were grouped in to classes according to ability (difficult to judge on a 2 minute audition, especially if you had travelled half way across the world) I remember clearly one girl who had travelled from Australia, totally jet lagged and within a few minutes of arriving had to audition and was dismissed as not worthy of the A or B class. She was devastated, but she was an incredibly talented player who has gone on to be hugely successful.

The class groups were A who played to Wibb and C&D who played to me and Kate Hill.

Many students said that they learnt the most from Kate and myself, because they had so much attention, we saw them and taught them every day, whereas the groups A and B sometimes only played once. And those students learning for fun were often made to feel worthless.

So addressing the negative parts of that course and turning them into positives helped conceive my own course. It was aimed at all ages and all abilities. I didn’t want to discriminate and as a result make people feel unwelcome or unworthy. You can learn just as much from a less able student as you can from a more advanced one. Basically if someone has the desire to learn then it was my job to help them.

I wanted to create a happy and relaxed environment, where you could learn without fear. I booked a very large house in the Lake District overlooking Bassenthwaite Lake, recruited my sister and a friend from college to do the cooking. I filled the common areas with flowers and sweets. We had a mixture of masterclasses, workshops, chamber music and individual lessons. Everyone was welcome and we tried to instil confidence, regardless of age or ability.

After a few years, J Myall of Just Flutes, said I should run the course further south and that’s when the Woldingham course began. It ran for 22 years and I think by the last course it was set up perfectly. We had Ian Clarke teaching alongside me, plus Gary Woolf, Louise Matthews, Tim Carey on piano and visitors including Wissam Boustany and Michael Cox. It was a wonderful experience and I loved every moment.

The “B” Word!

Big is best, big is beautiful, well actually no it isn’t!

What am I talking about? Volume of sound.

There always seems to be so much emphasis on making huge noises, to the detriment of beautiful ones. So many players can play loudly, but very few can play softly. Why? Well because playing softly requires refined technique and technique requires practice - lots of it! Playing loudly needs only large amounts of air. A simplistic view, but a fairly accurate one.

As performers, we are required to keep our listeners’ interest, by varying the colours, dynamics, vibrato and the emotions. It is the combination of all of these aspects, that help us sound beautiful.

I myself am a graduate of the big sound academy and remember the almost smug satisfaction of being able to “play out” with enough decibels to burst eardrums at 20 paces. How wrong and deluded I was, but I wasn’t alone and many players still spend endless amounts of practice trying to push their sound way beyond the beauty mark.

During my college years I quickly realised as I became more sound aware, that playing big was not enough and worked hard to create more beauty in my sound.

It is the projection of sound which is the key, not the volume.This projection is dependent on the resonance of the sound produced.

Resonance refers to the fullness of your tone and depends on the shape of the mouth cavities in which your sound can reverberate. If the resonance is missing, then your tone will be thin. Your flute, mouth, throat, sinuses and chest all act as resonators.

To help develop your resonance, you need to learn how to raise and lower the soft palette and be flexible in your embouchure shape, to create different spaces for your sound to resonate. Developing the core of your sound, or the centre, the most important part, is crucial. Just above that core you will have overtones and below the undertones. Being flexible is about changing the amount of harmonics, without losing the quality of the core. Blowing too much just sends the sound off into orbit!

So, flexibility and experimentation are crucial to help develop the sound, plus of course, your ears.

Now there is a danger of course, to go to the other extreme and sound too pretty. Any sound though that stays consistently the same, will lose it’s interest. The sound has to develop according to the demands of the music and in order to be convincing, the emotion behind the sound has to have the ability to communicate that music.

We all have the ability to sound individual by utilizing our own physical characteristics. In this way we become interesting to listen to, but if players overuse the amount of air, the result is an ugly beast of a sound.

Maybe we should start a new society, “The Beautiful Flute Sound Society”. How difficult it would be for so many players to gain an introduction to this society. It would be elite!

What is the answer then? I believe that flutists of all abilities, whether amateur or professional, should start to open up their ears and listen to how they sound. It is each individual’s responsibility to seek out and nurture the resonance within their tone. It’s simple, if you don’t sound good, nobody will want to listen.

Do you want to sound beautiful? Well go on then, do it!!

Big is best, big is beautiful, well actually no it isn’t!

What am I talking about? Volume of sound.

There always seems to be so much emphasis on making huge noises, to the detriment of beautiful ones. So many players can play loudly, but very few can play softly. Why? Well because playing softly requires refined technique and technique requires practice - lots of it! Playing loudly needs only large amounts of air. A simplistic view, but a fairly accurate one.

As performers, we are required to keep our listeners’ interest, by varying the colours, dynamics, vibrato and the emotions. It is the combination of all of these aspects, that help us sound beautiful.

I myself am a graduate of the big sound academy and remember the almost smug satisfaction of being able to “play out” with enough decibels to burst eardrums at 20 paces. How wrong and deluded I was, but I wasn’t alone and many players still spend endless amounts of practice trying to push their sound way beyond the beauty mark.

During my college years I quickly realised as I became more sound aware, that playing big was not enough and worked hard to create more beauty in my sound.

It is the projection of sound which is the key, not the volume.This projection is dependent on the resonance of the sound produced.

Resonance refers to the fullness of your tone and depends on the shape of the mouth cavities in which your sound can reverberate. If the resonance is missing, then your tone will be thin. Your flute, mouth, throat, sinuses and chest all act as resonators.

To help develop your resonance, you need to learn how to raise and lower the soft palette and be flexible in your embouchure shape, to create different spaces for your sound to resonate. Developing the core of your sound, or the centre, the most important part, is crucial. Just above that core you will have overtones and below the undertones. Being flexible is about changing the amount of harmonics, without losing the quality of the core. Blowing too much just sends the sound off into orbit!

So, flexibility and experimentation are crucial to help develop the sound, plus of course, your ears.

Now there is a danger of course, to go to the other extreme and sound too pretty. Any sound though that stays consistently the same, will lose it’s interest. The sound has to develop according to the demands of the music and in order to be convincing, the emotion behind the sound has to have the ability to communicate that music.

We all have the ability to sound individual by utilizing our own physical characteristics. In this way we become interesting to listen to, but if players overuse the amount of air, the result is an ugly beast of a sound.

Maybe we should start a new society, “The Beautiful Flute Sound Society”. How difficult it would be for so many players to gain an introduction to this society. It would be elite!

What is the answer then? I believe that flutists of all abilities, whether amateur or professional, should start to open up their ears and listen to how they sound. It is each individual’s responsibility to seek out and nurture the resonance within their tone. It’s simple, if you don’t sound good, nobody will want to listen.

Do you want to sound beautiful? Well go on then, do it!!

Welcome to the difficult subject matter of articulation.

There are so many factors involved and it’s difficult to know where to start and where to finish, but I will try and lead you through the complex world of tonguing.

So what is articulation? It is the use of the tongue to enable us to speak or play with clarity and so be understood by people listening to us. Almost all tutor books cover tone and technique before articulation. This is because articulation defines the beginning of a note and the success of the technique, is dependant on a solid sound production, with the coordination of the tongue, air stream and embouchure.

The tongue is not there to start and stop the note, but merely to clarify the start. If the tongue is used to stop the note, the airflow is affected and the quality of sound reduced. So the tongue defines the start of the note and shouldn’t stop the airflow or end the note.

Just as in speech it is the clarity of the articulation, which allows us to be understood. Articulation is our musical language.

Speech is a mixture of consonants and vowels. In flute playing it is a mixture of articulation and vowels. Vowels add an open and warm quality to your sound, whereas the articulation will create the drive and excitement.

I like to use string analogy when discussing articulation. Your tongue is the equivalent of the string player’s bow and your tummy muscles the string player’s arm. By imagining how a string player would bow a passage, which is visible, we can then be more creative in adapting the techniques we use, which are not visible. It’s not enough just to say “te”! We need to add as much variety to our articulation as a string player. So for example, the strength of attack, length of attack, the position of the tongue and the syllables we use.

Articulation is often ignored in the early learning process because there are so many other aspects of flute technique to think about and successful articulation only happens when the tone is well produced controlled by good breath control and even fingers. Try to have clear objectives before you start to practise articulation, rather than just tonguing and thinking that you will progress your level.

Are you practising to improve the clarity, speed, length, the dynamic or the variety, and there are so many varieties: single, double, triple, flutter, legato, staccato, staccatisimo, tenuto, accent, loure. So, so many!

We need to understand how we move the tongue, where it starts, how it moves where it finishes and the shape. We also have to think about which part of the tongue to use and where in the mouth to articulate.

There are two schools of technique in terms of where to tongue and they are based on speech and language. Flute players will normally and naturally tongue in the same place as their language dictates. In France the tendency is to tongue forward with the tongue between the lips. In England the tongue is further back and higher, hitting the roof of the mouth where the gum meets the teeth. Both techniques are successful, but being able to use both, will give you greater freedom and flexibility in performance.

The closer the articulation is to the mouth hole on the flute, the better the clarity.

Clarity is also affected by the amount of tongue used at the point of attack and the speed of attack. A more pointed tongue shape will add a crisper and clearer start, especially if co-ordinated with a faster movement.

Successful articulation can only be achieved through a variety of approach, and this variety of approach enables you to progress. Remember to try different techniques and listen to the results. If the results aren’t clear enough, then change something.

What to practise then?

Articulation practice should always start with tone production, because if the sound is not being produced well, then the articulation will not be clear.

You need to know what you sound like in a legato passage, so that you can recognise any loss of tone quality in an articulated passage. I use many different excerpts to practise, but one of my favourites is Paganini’s Moto Perpetuo.

Pick a few phrases and think about how to practise. You can find the sheet music easily on-line or pick something that you already have, that uses continuous movement.

So how to practise?

First play it very slowly and legato, all slurred. This is the time to concentrate on producing your best sound and most importantly your most expressive sound. What I mean by this is using your vibrato to create an expressive, warm and expansive tone. One of the commonest problems I hear when players articulate is that they forget to be expressive, so we hear “dead” articulation and not bright and “alive” articulation. Keep your fingers even and practise different dotted rhythms to help control your technique. If your fingers aren’t even, you cannot coordinate your tongue and fingers. When you’re happy that your tone and fingers are good, move on to the next stage, which is pulsing. Moto is in 4/4 time and uses semiquavers or 16thnotes. Using your tummy muscles, pulse the first note of each beat. Listen to your tone and make sure it sounds as good as when you’re playing legato. Now pulse the second note of each group only, then the third and finally the fourth. Pulsing helps make you aware of your tummy muscles, which support the breath and help maintain your tone. Little and often is the key to successful practice. Remember to pick just a few phrases at a time.

So this first phase of practising articulation, uses no tonguing at all, it’s just slurring everything but using your tummy muscles to pulse.

The nest step is to add the tongue. We add the tongue to the first note of each beat, alongside pulsing the first note of each beat. When you’ve mastered that stage, continue then to add the tongue to the second note of each beat only, then the third and finally the fourth.

The method now is to gradually take away the slurs, so that you end up tonguing all the notes. Starting with slurring groups of 2 semiquavers, keeping the air flowing, don’t let your tongue stop the airstream and very importantly, don’t shorten the slurs. Keep your ears open all the time. Now slur in groups of 3 semi’s with the last note articulated, then slur in 2’s with 2 notes articulated. Next slur 2 notes with 6 articulated and finally all articulated.

Ask your self: Do I sound the same as when I played legato? Am I engaging my tummy muscles? Am I keeping the full length of the notes and not shortening? Does the articulation sound clear? If it’s not clear, try changing the syllable: te, tuh, ta, tu. There are so many variables.

The problem from a teacher’s perspective, is that they cannot see inside your mouth to check where the tongue hits, and what shape it is. So each individual needs to experiment.

Articulation can have the effect of slowing down the tempo, whereas slurs can have the opposite effect of speeding up. So listen to the evenness of your fingers.

The other downside of articulation is that the tone can diminish, so practising different combinations of slurred and tongued notes can help the player hear if there is a difference in the tonal quality. In short, don’t let the articulation affect your tone or rhythm.

There are so many factors involved and it’s difficult to know where to start and where to finish, but I will try and lead you through the complex world of tonguing.

So what is articulation? It is the use of the tongue to enable us to speak or play with clarity and so be understood by people listening to us. Almost all tutor books cover tone and technique before articulation. This is because articulation defines the beginning of a note and the success of the technique, is dependant on a solid sound production, with the coordination of the tongue, air stream and embouchure.

The tongue is not there to start and stop the note, but merely to clarify the start. If the tongue is used to stop the note, the airflow is affected and the quality of sound reduced. So the tongue defines the start of the note and shouldn’t stop the airflow or end the note.

Just as in speech it is the clarity of the articulation, which allows us to be understood. Articulation is our musical language.

Speech is a mixture of consonants and vowels. In flute playing it is a mixture of articulation and vowels. Vowels add an open and warm quality to your sound, whereas the articulation will create the drive and excitement.

I like to use string analogy when discussing articulation. Your tongue is the equivalent of the string player’s bow and your tummy muscles the string player’s arm. By imagining how a string player would bow a passage, which is visible, we can then be more creative in adapting the techniques we use, which are not visible. It’s not enough just to say “te”! We need to add as much variety to our articulation as a string player. So for example, the strength of attack, length of attack, the position of the tongue and the syllables we use.

Articulation is often ignored in the early learning process because there are so many other aspects of flute technique to think about and successful articulation only happens when the tone is well produced controlled by good breath control and even fingers. Try to have clear objectives before you start to practise articulation, rather than just tonguing and thinking that you will progress your level.

Are you practising to improve the clarity, speed, length, the dynamic or the variety, and there are so many varieties: single, double, triple, flutter, legato, staccato, staccatisimo, tenuto, accent, loure. So, so many!

We need to understand how we move the tongue, where it starts, how it moves where it finishes and the shape. We also have to think about which part of the tongue to use and where in the mouth to articulate.

There are two schools of technique in terms of where to tongue and they are based on speech and language. Flute players will normally and naturally tongue in the same place as their language dictates. In France the tendency is to tongue forward with the tongue between the lips. In England the tongue is further back and higher, hitting the roof of the mouth where the gum meets the teeth. Both techniques are successful, but being able to use both, will give you greater freedom and flexibility in performance.

The closer the articulation is to the mouth hole on the flute, the better the clarity.

Clarity is also affected by the amount of tongue used at the point of attack and the speed of attack. A more pointed tongue shape will add a crisper and clearer start, especially if co-ordinated with a faster movement.

Successful articulation can only be achieved through a variety of approach, and this variety of approach enables you to progress. Remember to try different techniques and listen to the results. If the results aren’t clear enough, then change something.

What to practise then?

Articulation practice should always start with tone production, because if the sound is not being produced well, then the articulation will not be clear.

You need to know what you sound like in a legato passage, so that you can recognise any loss of tone quality in an articulated passage. I use many different excerpts to practise, but one of my favourites is Paganini’s Moto Perpetuo.

Pick a few phrases and think about how to practise. You can find the sheet music easily on-line or pick something that you already have, that uses continuous movement.

So how to practise?

First play it very slowly and legato, all slurred. This is the time to concentrate on producing your best sound and most importantly your most expressive sound. What I mean by this is using your vibrato to create an expressive, warm and expansive tone. One of the commonest problems I hear when players articulate is that they forget to be expressive, so we hear “dead” articulation and not bright and “alive” articulation. Keep your fingers even and practise different dotted rhythms to help control your technique. If your fingers aren’t even, you cannot coordinate your tongue and fingers. When you’re happy that your tone and fingers are good, move on to the next stage, which is pulsing. Moto is in 4/4 time and uses semiquavers or 16thnotes. Using your tummy muscles, pulse the first note of each beat. Listen to your tone and make sure it sounds as good as when you’re playing legato. Now pulse the second note of each group only, then the third and finally the fourth. Pulsing helps make you aware of your tummy muscles, which support the breath and help maintain your tone. Little and often is the key to successful practice. Remember to pick just a few phrases at a time.

So this first phase of practising articulation, uses no tonguing at all, it’s just slurring everything but using your tummy muscles to pulse.

The nest step is to add the tongue. We add the tongue to the first note of each beat, alongside pulsing the first note of each beat. When you’ve mastered that stage, continue then to add the tongue to the second note of each beat only, then the third and finally the fourth.

The method now is to gradually take away the slurs, so that you end up tonguing all the notes. Starting with slurring groups of 2 semiquavers, keeping the air flowing, don’t let your tongue stop the airstream and very importantly, don’t shorten the slurs. Keep your ears open all the time. Now slur in groups of 3 semi’s with the last note articulated, then slur in 2’s with 2 notes articulated. Next slur 2 notes with 6 articulated and finally all articulated.

Ask your self: Do I sound the same as when I played legato? Am I engaging my tummy muscles? Am I keeping the full length of the notes and not shortening? Does the articulation sound clear? If it’s not clear, try changing the syllable: te, tuh, ta, tu. There are so many variables.

The problem from a teacher’s perspective, is that they cannot see inside your mouth to check where the tongue hits, and what shape it is. So each individual needs to experiment.

Articulation can have the effect of slowing down the tempo, whereas slurs can have the opposite effect of speeding up. So listen to the evenness of your fingers.

The other downside of articulation is that the tone can diminish, so practising different combinations of slurred and tongued notes can help the player hear if there is a difference in the tonal quality. In short, don’t let the articulation affect your tone or rhythm.

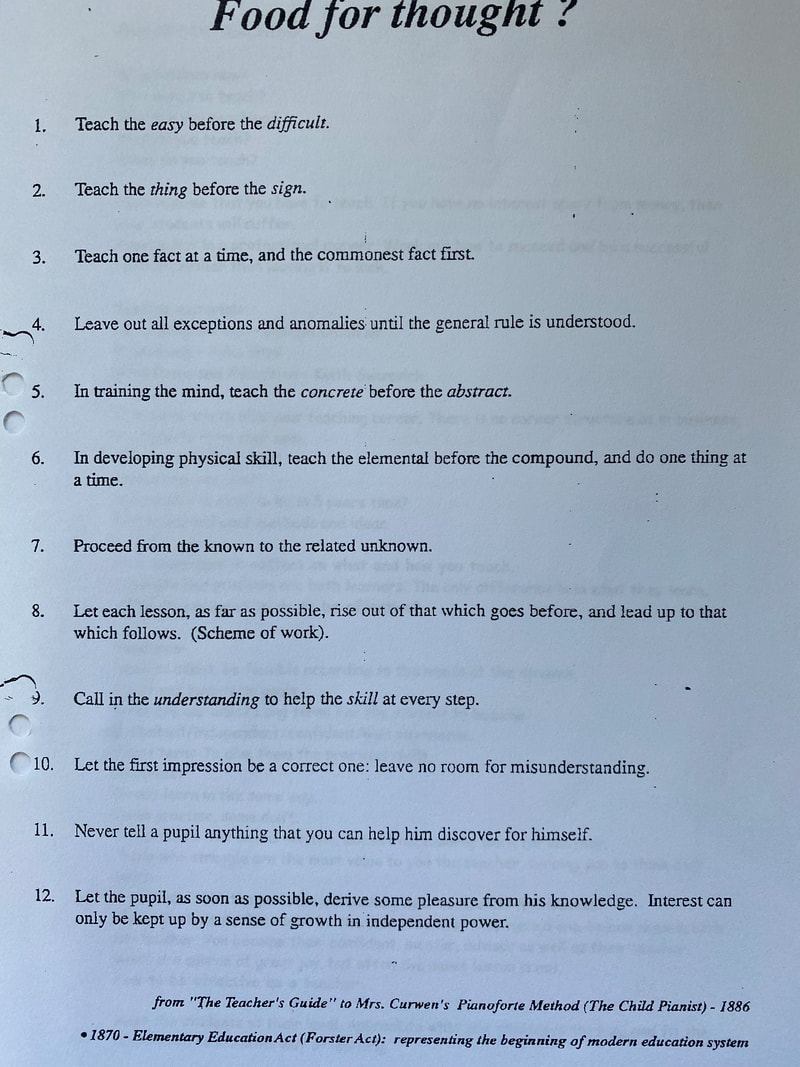

This fabulous list for teachers was published in 1886 in the Teacher's Guide to Mrs Curwen's pianoforte method. All her advice is totally applicable to our teaching today!!

Proudly powered by Weebly